It Takes a Village: Inciting Call to Action with Disease Prevention Outreach Programs Through Theoretical Foundation

In her 1996 book It Takes a Village, current presidential candidate and former United States Senator, First Lady, and Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton detailed her view that multiple determinants, such as community involvement, cultural/environmental influences and social interactions, contribute to how a child is raised. Similarly, inciting a consumer call to action with disease prevention outreach programs takes an amalgamation of different social and behavioral theories which rely on the same factors as the village concept. Studies assert that outreach programs based on more than one theoretical foundation, including Million Hearts which was established by combining the Health Belief Model (HBM) and the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), are more likely to produce a desired positive outcome than those that lack theory or are based on only one theory.

The Health Belief Model

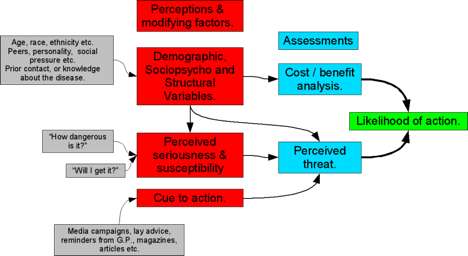

The first social behavioral theoretical foundation, Health Belief Model (HBM), emphasizes that the willingness to take action and prevent risk depends upon the beliefs about the susceptibility and severity of disease; the perceptions about the benefits and barriers; cues to action and self-efficacy.

In a hypertension prevention study, Hispanic respondents not only misperceived that certain behaviors are barriers that would increase their risk factors, but also expressed a lack of confidence in their ability to perform such behaviors as having their BP checked regularly, limiting their salt intake, eating five or more servings of fruit and vegetables daily, exercising at least 30 minutes four or more days of the week, and controlling their weight. The general perception that hypertension was not a severe disease and the susceptibility misunderstanding resulted in 68.6% of the respondents being at increased risk for developing hypertension.

The Theory of Planned Behavior

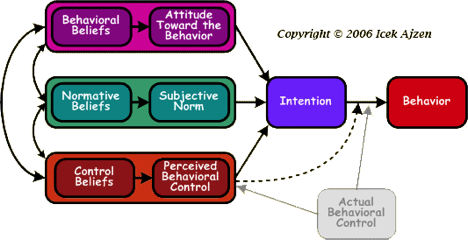

The second social behavioral theoretical foundation, Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), assumes that attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control predict actual behavior. Attitude refers to beliefs merged with the value placed on the behavioral performance outcome. Subjective norm signifies the perception of the social expectations to adopt a specific behavior. Perceived behavioral control reflects the beliefs about the level of ease or difficulty of performance behavior.

A circle of culture surfaced in a hypertension prevention study concerning poor eating patterns passed from generation to generation; physician distrust and questioning reasons doctors would want to lower BP because of the belief that physicians would not have a job if they addressed this health issue; and an unwelcome move that changes consumers from insiders to outsiders when they act differently by engaging in healthy behaviors. Severing cultural traditions and adopting preventive behaviors suggested by health care professionals resulted in social pressures.

Combining HBM & TPB: The Million Hearts™ Program

The Million Hearts™ national outreach program engages Community Health Workers (CHWs) to help achieve the goal of preventing one million heart attacks and strokes in the United States by 2017. The CHWs educate consumers about the importance of fit lifestyles and specifically promote these tenets for maintaining a healthy BP:

1) Having routine screenings for high BP;

2) Understanding BP numbers and the significance of lowering BP while searching for economical ways to increase lower sodium and whole grain foods and still keep their weight within BMI;

3) Comprehending the ramifications of uncontrolled BP that include damage to eyes, kidneys, heart blood vessels, and brain; high risk of heart attack and stroke; and chronic kidney failure requiring dialysis.

CHWs encourage consumers to interact with other members of the community including their physicians about clearly defined health goals and keep a daily record of BP readings to track progress. CHWs also introduce consumers to social workers and others who can teach them how to apply for programs and insurance that help pay for health care. Many Hispanic consumers prefer to learn information with plain language fotonovelas, similar to comic books, which are common in the culture. Personal interaction is carried out by “promotoras” from the same ethnic background who honor the tradition of reading a fotonovela with consumers.

- Controlling Hypertension by Learning to Control Sodium Intake: A Fotonovela

- Spanish Version: Cómo Controlar su Hipertensión: Aprenda a controlar su consumo de sodio

In summary, creating a consumer call to action with disease prevention outreach programs such as a Million Hearts™ takes a village of community involvement, cultural/environmental influences and social interactions supported by different theories including HBM and TPB. The underlying premise is that a combination of theories informs the message. Theories determine why, what, and how a health issue should be addressed and assist in developing successful program strategies that reach targeted priority populations to affect a positive impact.

References:

Del Pilar Rocha-Goldberg, María et al. “Hypertension Improvement Project (HIP) Latino: Results of a Pilot Study of Lifestyle Intervention for Lowering Blood Pressure in Latino Adults.” Ethnicity & Health 15.3 (2010): 269–282. PMC. Web. 19 May 2015.

Glanz, Karen, Rimer, Barbara K., andViswanath, K. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice (4th ed). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. 2008.

Noar, Seth M., Chabot, Melissa, and Zimmerman, Richard S. “Applying Health Behavior Theory to Multiple Behavior Change: Considerations and Approaches.” Prevention Medicine. Volume 46. March 2008.

Peters, Rosalind M., and Thomas N. Templin. “Theory of Planned Behavior, Self-Care Motivation, and Blood Pressure Self-Care.” Research and Theory for Nursing Practice 24.3 (2010): 172–186.

Peters, Rosalind M., Karen J. Aroian, and John M. Flack. “African American Culture and Hypertension Prevention.” Western Journal of Nursing Research 28.7 (2006): 831–863. PMC. Web. 19 May 2015.